James F. Downes

(Visiting Scholar, European Union Academic Programme Hong Kong)

There was much talk in the run up to the Dutch Election about the rise of the populist far right Freedom Party (PVV), particularly amongst international commentators. Under the leadership of the charismatic Geert Wilders, the narrative in the international media was that this party was going to create a political earthquake in the 15th March election. Such a narrative was arguably misplaced and did not accurately portray what was going on in the Netherlands. This commentary also did not understand the complex political system and coalition formation that is commonplace in the Dutch political system.

Exit poll results have instead shown a much broader and more nuanced picture overall. A bitesize summary of the early numbers behind the election is provided below:

(1) This was the highest turnout in 31 years at 82% (Ipsos Exit Poll)

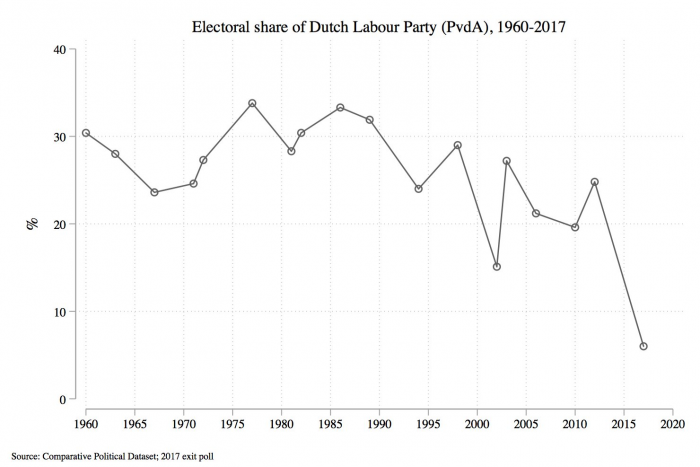

(2) Economic conditions were generally very good. However there was a large anti-incumbency vote (particularly for the Dutch Labour Party PvdA whose vote share declined by -29% points from the 2012 election). The center right VVD led by Prime Minister Mark Rutte saw their vote share decline by -10% points, but the party remains the biggest party in the Netherlands and can call the shots in the coming coalition talks.

(3) The PVV political earthquake did not materialize. Yes the party is the second largest now in terms of their seats in the Dutch Parliament, but their vote share only increased by 4%. This is considerably less than what was forecasted. The PVV will not be able to enter into any coalition talks as the main political parties have already ruled this out. Geert Wilders’ party is likely to remain on the sidelines and in opposition for the foreseeable future.

(4) The biggest electoral gainers was the Green Left (vote share increase of 12%) and D66 (vote share increase of 7%). Both parties arguably benefited from the wider anti-incumbency vote and most likely took voters off the PVDA. It is also important to note that both Green Left and D66 campaigned heavily on a pro-EU programme.

(5) The PvdA suffered its worst electoral result and must now regroup quickly, or face greater erosion of its support base from both Green Left and D66. Clearly, there has been a splintering of traditional mainstream parties over the last decade in the Netherlands and smaller parties have picked up votes from this splintering effect. The chart (1960-2017) shows the systematic electoral decline of the PvdA and should be a wake-up call for the party.

Figure 1- Electoral share of Dutch Labour Party (PvDA), 1960-2017

Early indications for the Dutch election highlight a complex picture that extends far beyond the narrative of a political earthquake for the far right PVV party. With the Brexit vote last year on the 23rd June and the forthcoming French Presidential election, there has been much talk about a domino effect occurring in Western European politics. However, this is clearly not the case in the Netherlands, with Wilders’ party facing further time in opposition. The historian Richard Hofstadter once remarked that ‘Far Right Parties are like bees, once they sting they die.’ In the case of the Netherlands, the sting may have already taken place and the ship may have now sailed for Geert Wilders and any chances he may have had of creating a political earthquake in the Netherlands. The center right VVD party has emerged as the biggest party with 33 seats (a loss of 8 MP’s), yet will now need to enter into coalition talks with other parties to form a new government. As is common in the Netherlands political system of power sharing, these talks are likely to last for a considerable degree of time, potentially weeks and even months. With the French Presidential election taking place next month, the Dutch election results are a timely reminder that the far right insurgency has not yet materialized on a large scale across Europe.